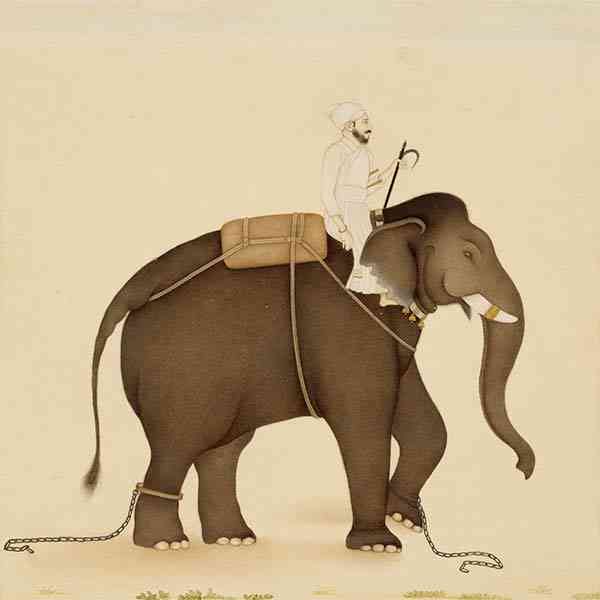

The Elephant and the Rider

A foundational truth of modern psychology: your mind is divided into parts that often conflict. If you’ve ever procrastinated, contacted an ex, or over-indulged, you already know this.

Your conscious, rational mind wants to lose weight and knows that you should skip dessert. Meanwhile, your automatic, emotional mind gets a sudden craving for chocolate, and before you know it, you’re staring at an empty candy wrapper.

There are many metaphors to explain this dichotomy - the emotional vs rational mind, Freud’s id vs superego, left vs right brain. But there’s no better (i.e., more useful) metaphor than Jonathan Haidt’s “the elephant and the rider” from his book The Happiness Hypothesis.

Take a look at this image. The rider is your conscious will - looking out over the horizon, seeing the land of ‘weight loss’, and doing his best to steer the elephant in the right direction.

The elephant is your automatic, emotional system - it is a ten thousand pound beast, somewhat aware of the rider, but more focused on its immediate surroundings. It ultimately decides where it wants to go. If the rider and elephant disagree, the elephant wins.

You probably identify more with the rider - it is the voice in your head, after all. And it’s easy to place the rider above the elephant (both literally and metaphorically) - most modern influencers appeal to the rider and liken the ‘conscious mind’ to a CEO, the one in charge, recommending that you simply learn to make the emotional side bend to your will. But behavioral psychologists see it as reversed. The rider evolved to serve the elephant, not the other way around.

The vast majority of our decisions and behaviors come from the elephant. Our conscious reasoning is limited - we can only think of one thing at a time - while our automatic processes are running in parallel, deciding how to move, what to eat, where to go, etc. Our intuitions, emotions, defaults, visceral reactions, and gut feelings all come from the elephant. Without these automatic processes, every single task and decision would be painstaking and difficult. In fact, the beauty of habits is that it makes beneficial behaviors automatic.

The rider and elephant metaphor is so useful because it gives proper respect to both systems. The rider cannot control the elephant, but it can distract, coax, guide the elephant with the right approach. You will never overwhelm the elephant in a contest of wills, but you can steer and nudge the elephant if you’re smart about it.

Once you realize that you are both the elephant and the rider, you’ll find it much easier to change directions.